Like an empty cross

Stands the lone cold wick.

Like a cold bare tomb

The fire’s grate.

The flame recalled, in hope no doubt,

Rising from the ashes of the light snuffed out.

(Words for lighting the candle in the chalice)

Last Sunday, Easter Sunday, we included physical ritual in our gathering for the first time since the COVID19 pandemic, and it’s a sign that we in Ringwood are at last throwing off the mental shackles associated with the pandemic, and getting back to how we were before it all started.

In a reflective and meditative service, we built on our overall approach to the Gospel — and, in particular, the book attributed to Mark — as ‘shared story’ for personal reflection. In this service, the ‘shared story’ vehicle for the reflection and meditation was not a Bible reading, but instead a version of the 'Stations of the Cross' meditation, used for hundreds of years in various Christian traditions.

There were only a few words offered as content, those being the words used at lighting the candle in the chalice, and the words used as the response for the prayer at each station.

Leader: "With compassion we gaze on thy story.

Response: "Because in it we see something of the world."

Rather than being a wordy service, there was much time for personal quiet. Participants were invited to picture the moment at each station, and let our reflection go where it will. Recorded chants from the Taizé-style of worship were also played during the ritual. Traditionally, inside a church building the Stations of the Cross would be carried out by walking to a series of physical locations in the church. But with all our participants seated in a circle, our president for the day decided to mark each of the fourteen stations by passing a candle round the full circle, hand to hand.

"I have come to feel that [rituals] have another purpose — to end, for a time, our sense of human alienation from nature and from each other…….Rituals have the power to reset the terms of our universe until we find ourselves suddenly and truly at home."

Margot Adler, Drawing Down the Moon

"Any ritual is an opportunity for transformation. To do ritual, you must be willing to be transformed in some way. That inner willingness is what makes the ritual come alive and have power. If you aren’t willing to be changed by the ritual, don’t do it."

Starhawk, Truth or Dare

To this last quote, we would add: if you aren't willing to be changed by the ritual, you are not, in fact, doing the ritual (no matter that it looks like you are).

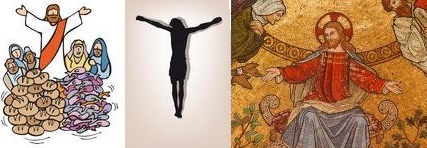

Stations of the Cross (source: Wikipedia, adapted)

The Stations of the Cross or the Way of the Cross, also known as the Way of Sorrows or the Via Crucis, refers to a series of images depicting Jesus on the day of his crucifixion, and accompanying prayers.

The Stations of the Cross ritual has existed in one form or another for at least five hundred years. The earliest use of the word "stations", as applied to the accustomed halting-places along the Via Sacra at Jerusalem, occurs in the narrative of an English pilgrim, William Wey, who visited the Holy Land in the mid-15th century and described pilgrims following the footsteps of Jesus to Golgotha. It has become one of the most popular devotions and the stations can be found in many Western Christian churches, including those in the Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Anglican, and Methodist traditions.

Out of the fourteen traditional Stations of the Cross, only eight have a clear scriptural foundation. To provide a version of this devotion more closely aligned with the biblical accounts, Pope John Paul II introduced a new form of devotion, called the Scriptural Way of the Cross, on Good Friday 1991.