The July gathering was an interesting confluence of ancient and bang-up-to-date streams of thought. It was held on 11 July, which has traditionally been marked as the feast of Benedict of Nursia, whose organised rules for living monastically, written in the sixth century, have been handed down and continue to influence monastic living today. Benedict’s insights on living in community today also influence thought-streams in the spheres of business management and personal improvement. That was the ancient bit. And the up-to-the-minute bit was: raising the topic of what it means to live in community is particularly appropriate in these days of hybrid living — part face-to-face and part online, and trying to sustain long-distance relationships.

We had some singing together in the way we all do on Zoom: all muted, but each hearing the lead musicians; we listened to some recordings by musicians on YouTube; we used this month’s chalice lighting words from the International Council of Unitarians and Universalists; we held our seven minutes of silence; and we spoke together the version of words of shared affirmation that are becoming a regular feature of our gathered time together.

YouTube music:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8oBFBW7zQn8

There were two readings, one from Bill Houff, a Unitarian Universalist in the USA, and the second from what would normally be called the book of James, in the New Testament of the Bible, but which ought to be known as the letter of Jacob.

Bill Houff spoke of the discipline needed for spiritual growth but also of the ordinariness of the spiritual life, and cited the following well-known story from Zen Buddhism:

A particularly eager spiritual novice went to the master of a monastery and said, “I am ready for every sacrifice; please teach me the way.”

“Have you eaten your rice porridge?” asked the master.

“Yes,” replied the student, “I have eaten.”

“Then you had better wash your bowl,” said the master.

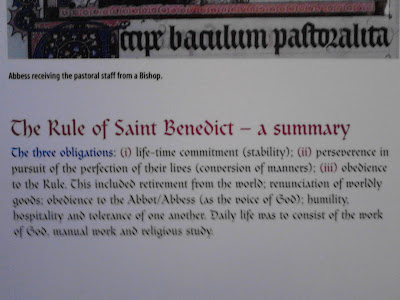

The reflection by the president of the day wandered through the 'family tree' of western Christian monasticism, starting with the apostles Paul and James (who as mentioned above, might better be known in the English-speaking world as Jacob) living in a rural region outside Jerusalem, moving through the Desert Fathers and Mothers in Egypt, John Cassian of Romania, and finishing up with Benedict of Nursia. Much use was made of the following reference sources, which are not associated with any religious institution but instead are academic historical researches:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_the_Apostle

https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/bible-versions-and-translations/james-or-jacob-in-the-bible/

https://www.biblestudytools.com/gnt/james/

https://www.bibleodyssey.org/people/related-articles/james-and-paul

The reflection also looked at the message of James/Jacob, as it eventually emerged through the Benedictine order in western Europe. It was suggested that the most important point carried down through the generations is why the church places such importance on long-lived relationships and commitments, and how that is related to the ordinariness of spiritual growth in community — the need to wash the rice bowl. It was summed up in some words from Rowan Williams:

“The church celebrates fidelity....it lives by the regular round of worship — the daily prayer of believers...meeting the same potentially difficult or unexciting people time after time, because they are the soil of growth.”

The president concluded: “It’s hard in UK to be a Unitarian. Our communities are so small and so thinly scattered, we all have to travel such distances. But it’s even harder to be a Unitarian completely on your own. That’s because the mark of a Unitarian is they are someone who has seen that it’s not enough to be a solo seeker. A Unitarian may start on their own but, if my experience is anything to go by, they get lonely, and they see and yearn for the gifts of learning and sustaining inner growth through the company of others.

"Learning and sustaining requires trust. Trust is only built via travelling a bumpy road together, with persistence, humour, humility and generosity. It takes time. And these days, thankfully we have an online space that allows us to continue along our bumpy road, no matter how far apart we physically live. The mark of Unitarians is living in community, and today we celebrate the life of Benedict, who had a great deal to say on the subject.”