“I believe…”

I’m going to ask you to bear with me. There are going to be times you want to jump in and point out things that are problematic, things you don’t agree with, things that need rounding off or balancing out. Don’t do it. I won’t take your silence for agreement and I ask you to not take any of mine for deliberate avoidance or ‘tacit denial’. I’m going to advance a position today that suggests that what we say takes its meaning from the conversation we are having, and that that conversation is framed within the community, culture, and ‘way of life’ we find ourselves in. This isn’t my idea, so I am not going to build it up from the foundations. If you fancy checking it out in detail give Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations a look.

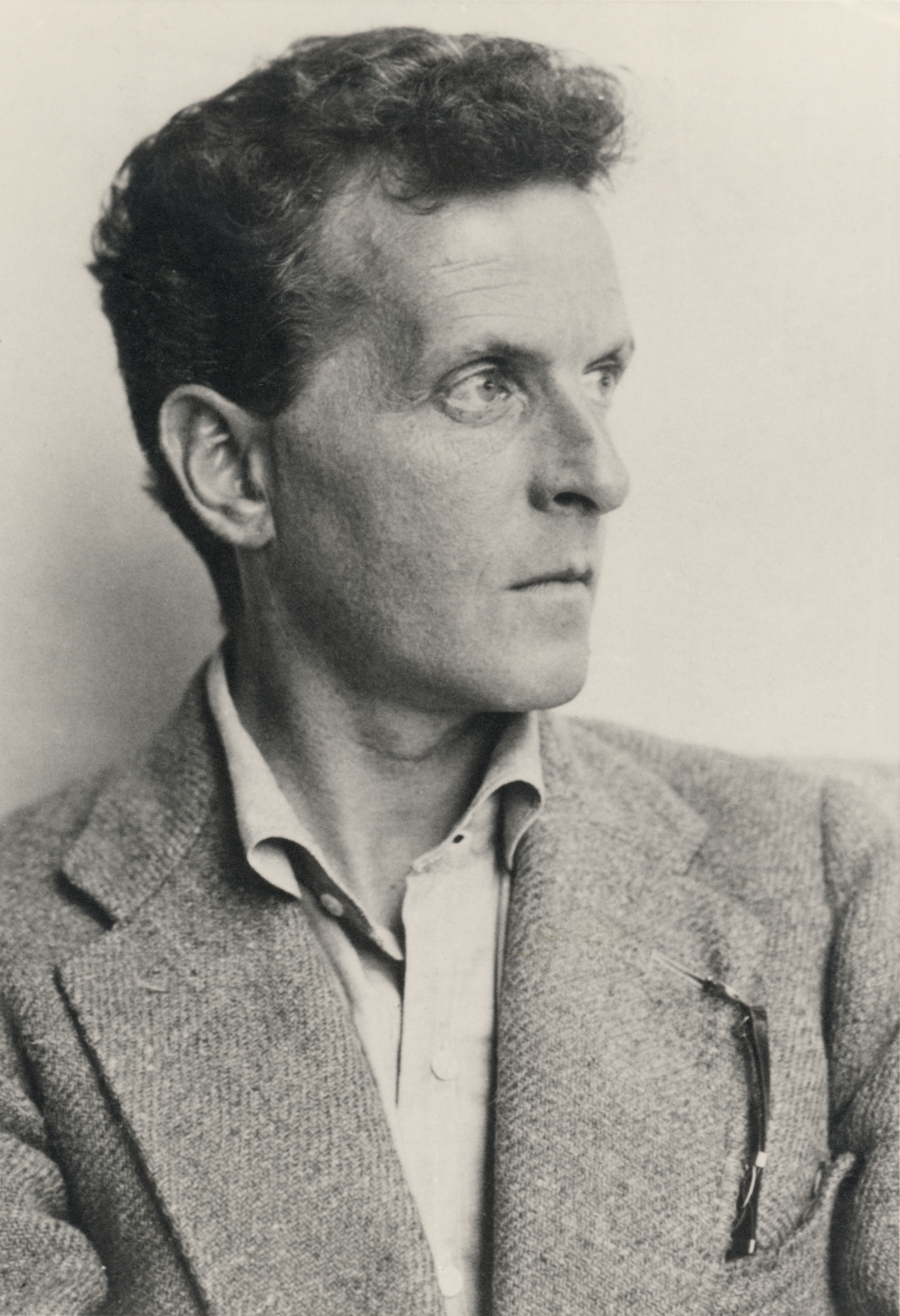

|

| Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1930 |

The meaning I am looking for today is what we mean when we talk about our beliefs, how we understand what is said when we say “I believe…” or, I guess more often today, when we say “I don’t believe…”.

These kinds of statements, even when made in private, always have an audience, either actually there or imagined. First off, we are saying them in a language that we have learned from others and use within a community.

We don’t get to decide what a word means or how a language works, no matter how much we can push the boundaries of it. The more we nudge words outside their usual use the less likely our audience will understand what we mean, and the harder time we will have being sure we know what we mean ourselves. Sound extreme? Ask yourself how clear you are on something when you can’t share it with anyone else. If you find yourself unable to describe it, explain it, or even show it, then you are going to have some doubts about it.

I spoke about nudging ‘words outside their usual use’. We don’t learn language by understanding what one word means using a series of others. We would never be able to begin, if that was how language worked. We don’t learn language by clearly setting out and agreeing on terms up front; we need to already have language to be able to do that. Rather, we learn language by doing things. We learn to sit in chairs, to pass the sugar, to find the bathroom; and the more we do things with others the more our language grows, and the more complicated the things we do as a group, the more complicated our language becomes. This starts right from our first words and carries on throughout our lives. We’ve all started a new job and felt a bit lost till we were in on the buzzwords and shortenings; we’ve all taken up a hobby and at first felt bewildered by the array of new terms and phrases. Those of us who have lived abroad and learnt a new language will recall how we moved from translating every foreign word back into a word from our mother tongue, and finally came to a place we could say and think and even feel things in the new language that we were unable to quite express in our first one.

|

| This fascinating book says a lot more about how languages don't exactly match. |

I’ve dwelt on this longer than I intended, but it is important because when we say “I believe...” we are saying it not just in our mother tongue, we are saying it in a certain ‘work’ or ‘hobby’ environment too. We are saying it in the context of doing something together, simple or very complex: we are saying it in the context of doing something. If what I am doing and what you are doing are not the same, if I am talking in terms of one environment and you in terms of another, then we may as well be talking two different languages.

When we say “I believe…” we are conversing within a community and we are trying to do something specific within that conversation. When we fail to acknowledge that community and to accept what is being aimed at we cut ourselves off from conversation and can only enter into conflict. At the heart of that conflict is the need to impose on the other what we understand by the words they are using, and that need is driven by the deep desire to understand ourselves. Socrates, in Plato’s dialogue Alcibiades I, speaks of how we see ourselves in the mirror that is the eyes of others. Well: imposing what we want words to mean is rather like painting over that mirror with the portrait we’d like to see. When we succeed in doing it, we harm the other and lose sight of ourselves as well.

|

| "The Portrait of Dorian Gray" by Oscar Wilde |

If we are going to have fruitful conversations around what we believe — and even more so if we are going to build fruitful communities around what we believe — we need to learn to look into the eyes of others. We need to realise that belief is something that isn’t about the sound of words or how we try to draw out the concepts; it’s about how we live.

In the Bible, ‘truth’ is something that is done not just said; knowing is about relationships, not just being right and being able to explain why. I bring up the Bible here, not to rely on its authority, but because it relays thousands of years of human religious experience and because it is central to the community and culture in which many of us, myself most certainly, talk about our beliefs. Whether we say “I believe …” or “I don’t believe …” we, here in the West, are talking in the shadow of that dominant narrative. Our communities have splintered into smaller communities each with their own divergent stance to that narrative, but it is there for the Atheist Humanist, the Pagan Revivalist, and the Cultural Agnostic, as much as for the Roman Catholic, Protestant, or Non-Conformist.

Acknowledging the role of language, and its reliance on communities and what we are trying to do at any given time, might sound like it is making saying “I believe...” difficult, like it’s making the conversation around that nigh-on impossible, but it isn’t. All our language is rooted in the experiences we share, the things we can and can’t do, the world we live in as ourselves, the things we can’t change that set the stage for the things we can. Language works, for all its nuance and contextuality, because language is how we live in a world we share. We can say “I believe…” because of that shared world, that shared experience, that shared interplay of what we can and can’t change.

If we put in the work to understand the conversation that is being had when we say “I believe …”, if we can hold back with pushing what we think ‘should’ be meant with the words, if we can actually engage with what is trying to be done in that moment, then we can begin to grow together and in looking into another’s eyes we can begin to see ourselves better too.

Belief is never purely intellectual: it is about how we live our lives, why we make our choices. I hope we can explore that together, I hope we can share that together, and I know that if we do together, we’ll find that our language will bring us eventually more together, however much it may hold us apart for now.

No comments:

Post a Comment

We welcome your enquiry and like to converse. This is where we set out some of what we offer. If you don't like what you read, scroll on by. We reserve the right to disregard unappreciative audiences.

Any personal email addresses supplied in your comments will be removed from posts during the moderation process to protect your data.